Integrated plan with live production needed to meet new Salmonella standards

Poultry companies struggling to meet higher USDA standards for Salmonella need to increase control efforts in live production to help avoid dreaded Category 3 designations as well as potential regulatory action that could shake customer confidence.

“Processing can’t do it all,” insisted Douglas L. Fulnechek, DVM, who spent 28 years with USDA Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) before joining the animal-health company Zoetis in 2016 as senior public health veterinarian.

“For poultry companies to meet today’s rigorous USDA/FSIS standards, there needs to be a comprehensive, integrated plan involving live production and processing to minimize the presence of Salmonella throughout the entire operation. Everyone needs to be part of the solution,” he said.

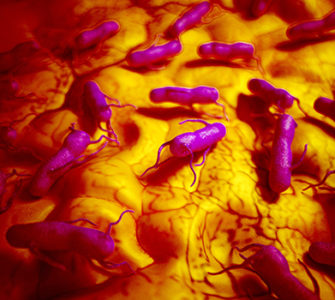

Ubiquitous bacterium

Speaking at a news conference, Fulnechek noted that Salmonella is a naturally occurring, ubiquitous bacterium in poultry intestines — one found in commercial and backyard flocks alike. It can be present in perfectly healthy birds with no negative health effects.1

Breeder hens can spread Salmonella vertically to offspring. Salmonella can then spread horizontally, from one chicken to another.2 Chickens can also contract Salmonella from wildlife, rodents, insects, litter, water, feed, equipment and people,3 he said.

“Live production is where the pathogen is most likely to start, so that’s where control measures need to get started as well — beginning with the breeder flock and then extending control through the hatchery and onto the broiler farms,” Fulnechek added.

“Post-harvest controls are critical, too,” he added, “but the processing plant should be viewed as the last chance for Salmonella control — not the first.”

The US poultry industry has responded positively to the new USDA/FSIS standards by demonstrating substantial declines in Salmonella and fewer plants rated by the agency as Category 3 for failing to meet the new standards.

For example:

• Between December 31, 2017 and December 29, 2018, 15.05% of 186 processing plants were in Category 3 for chicken carcasses, compared to 16.58% of 186 plants in the agency’s previous year-end report, which included data from October 9, 2016 through December 30, 2017.

• For chicken parts, 22.47% of 267 plants were in Category 3, compared to 36.84% of 285 plants in the previous year-end report. (Table 1.)

Vaccination up

Don Waldrip, DVM, a technical service veterinarian for Zoetis with more than five decades’ experience managing poultry pathogens, said US poultry companies need to start putting as much focus on controlling Salmonella in live production — in the breeder flock, as well as the hatchery and broiler farms — as they traditionally have during processing.

Pointing to studies demonstrating that broiler chickens from hens vaccinated for Salmonella have less of the pathogen at processing compared to broilers from unvaccinated hens,4 Waldrip said more poultry companies have turned to vaccinating their breeder hens — and more often.

He cited statistics from Rennier Associates, Inc., Columbia, Missouri, a firm that tracks and monitors animal health-product usage in the U.S. poultry industry, that showed at least 70% of broiler breeder flocks were vaccinated at least twice for Salmonella in 2017 (the most recent year statistics are available) — up from 23% in 2010. More than 35% of broiler breeders were vaccinated four or more times, up from 20% in the same period.5

Charles Hofacre, DVM, PhD, president of the Southern Poultry Research Group Inc., Athens, Georgia, said the surge in breeder-flock vaccination was a positive trend.

“Salmonella in breeders is like a drippy faucet,” he added. “If it keeps dripping into broilers, it makes the level high enough that the processing plant has trouble meeting its goals and targets. Most poultry companies now realize it’s better to focus on breeder vaccination and get ahead of the game.”

New focus on broilers

Aware of recent studies6,7 showing broiler vaccination could help reduce the load of Salmonella going into the plant, many poultry companies are now vaccinating broiler flocks as well. Waldrip cited data from Rennier Associates showing that sales of Salmonella vaccines for broilers in 2017 (the most recent year available) skyrocketed 5,900% over 2015.

While broiler vaccination is an added expense, Hofacre said it’s a good investment when “there’s a high load of Salmonella coming into the processing plant — more than the plant can deal with.” It’s also a good option when foodborne types of Salmonella that affect human health, such as S. Heidelberg, S. Typhimurium or S. Enteritidis, are identified in the system.

Despite the poultry industry’s stepped-up efforts to vaccinate for Salmonella, the specialists cautioned that vaccination can’t do it alone. Improvements in other areas of live production — biosecurity, sanitation, egg handling at the hatchery, litter management, pest control, ventilation, stocking density, feed withdrawal, drinking-water acidification and control of enteric diseases (coccidiosis, necrotic enteritis) — are also needed to reduce the Salmonella load going into the processing plant.

Furthermore, making improvements in overall flock health can reduce opportunities for Salmonella to colonize and spread. “One way to reduce foodborne pathogen levels in the plant is to reduce subclinical illness and overall disease in live poultry,” said Hofacre, who is also professor emeritus at the University of Georgia.

Unhealthy birds, he added, are going to be less uniform in size, possibly with more nicked intestines and fecal contamination, which can result in a greater opportunity for Salmonella to contaminate the carcass, he added.

More communication

The veterinarians noted that more and regular communication between live production and processing was essential to reducing Salmonella. That’s easier said than done, however, because the two segments usually operate as separate profit centers. Furthermore, controlling Salmonella yields little to no performance benefits in live production, so production managers are naturally reluctant to increase costs without seeing measurable returns.

“That was a problem in the past, but I think that mindset is starting to change,” Hofacre said. “Complex managers know investments made in Salmonella control during live production won’t net returns until processing, so this group is critical in helping poultry companies look at the big picture.”

He noted that with poultry companies leaning more on vaccination and other practices to reduce Salmonella in live production, those expenses show up in the Agri Stats reports that poultry companies use to benchmark their production efficiencies against the rest of the industry.

“That added production expense for Salmonella doesn’t stick out on the report the way it did a few years ago,” Hofacre said. “Poultry companies understand that’s now the cost of doing business.”

Teaming up

The increased pressure on poultry companies to control Salmonella prompted Zoetis to reorganize its technical services team to focus more on food safety, said Jeff Sizelove, senior vice president, US poultry, Zoetis.

For example, Zoetis technical service veterinarians are now frequently seen in processing plants as well as in live production. “They typically start with the breeder flock, follow the eggs into the hatchery and then follow the progeny onto the broiler farms and into the plant,” he said. “Recommendations are then tailored to suit each operation’s needs and practices.”

The company’s focus on food safety isn’t limited to poultry, however. He noted that in 2015, Zoetis added a line of antimicrobials and other food-safety agents for poultry, pork and beef processing plants.

“We wanted to combine Zoetis’ more than 60 years of animal-health experience with proven processing interventions to help producers take a more holistic, integrated approach to food safety through every step of the production cycle,” Sizelove explained.

Avoiding the dreaded Category 3

Focusing on Salmonella control during live production is especially critical now with increased pressure from USDA’s Food Safety and Inspective Service (FSIS) Salmonella Verification Program, said Douglas L. Fulnechek, DVM, senior public health veterinarian, Zoetis.

According to the National Chicken Council, there are more than 2,000 different strains of Salmonella — the majority of which are not harmful to humans.8 Nevertheless, any samples positive for the pathogen count against the plant. After all, Fulnechek reasoned, if a harmless type of Salmonella can get through the system, so can potentially harmful ones.

FSIS tests primarily whole carcasses and chicken parts for Salmonella, and there are different allowable limits for each. Based on results over a 52-week testing period, the agency puts plants in one of three categories for Salmonella compliance. (Table 1.)

Category 1, the most desirable rating, means a processing plant has less than half of the Salmonella expected. Plants in Category 2 have more Salmonella than plants in Category 1 but still meet the government standards. Category 3 means a plant has more Salmonella than allowed for carcasses, parts or both.

High stakes

“Category 3 is where it gets really worrisome,” Fulnechek said. “FSIS is now publishing its test results online and they are available to anyone. Besides eroding your customers’ confidence, a Category 3 designation could potentially decrease your export opportunities to markets with more stringent rules for Salmonella.”

Even worse, he added, if FSIS finds upon resampling that plants in Category 3 have not taken adequate corrective action, the agency could suspend inspections, which essentially shuts down the plant because meat sold to the public has to be inspected.

Corrective actions can be a combination of things, Fulnechek said, but FSIS will want to see action taken at the plant, where it has authority. An example of a corrective action would be adding an antimicrobial dip after evisceration or after picking or chilling.

“In some cases, a plant is doing all that it can but is still in Category 3, and this is where it’s especially important for live production to lower the load of Salmonella going into the plant,” he added, “because the plant obviously can’t handle the load of Salmonella it’s getting.”

Table 1. FSIS results for chicken carcasses and parts show a reduction in the number of plants in Category 3.

Table 2. FSIS Salmonella standards

- Questions & Answers about Salmonella, National Chicken Council. https://www.nationalchickencouncil.org/questions-answers-about-salmonella/ Accessed Jan. 24, 2019.

- Liljebelke KA. Vertical and horizontal transmission of Salmonella within integrated broiler system. https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/abs/10.1089/fpd.2005.2.90 Accessed Jan. 24, 2019

- Trampel DW. Integrated farm management to prevent Salmonella Enteritidis contamination of eggs. https://academic.oup.com/japr/article/23/2/353/762531 Accessed Jan. 29, 2019

- Dorea FC, et al. Effect of Salmonella Vaccination of Breeder Chickens onContamination of Broiler Chicken Carcasses in Integrated Poultry Operations. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010 Dec;7820-7825.

- Rennier Associates, Salmonella Vaccination Programs (Broiler Breeders), slide 85.

- Data on file, Study Report No. 04-16-7ADMJ, Zoetis LLC.

- Data on file, Study Report No. 04-16-7ADMJ, Zoetis LLC.

- Questions & Answers about Salmonella, National Chicken Council. https://www.nationalchickencouncil.org/questions-answers-about-salmonella/ Accessed Jan. 24, 2019.

- USDA FSIS. https://www.fsis.usda.gov/wps/wcm/connect/7e1608c9-bb5b-4515-9a04-e4b6dac11866/establishment-categories-aggregate-201801.pdf?MOD=AJPERES Accessed: Feb. 6, 2019

- USDA FSIS. https://www.fsis.usda.gov/wps/wcm/connect/32c7c17a-84ba-4d45-996c-fae7df0a9b6b/establishment-categories-aggregate-201901.pdf?MOD=AJPERES Accessed Feb. 6, 2019

- Salmonella Pathogen Reduction Performance Standard — an Explanation, January 2019, National Chicken Council. https://www.nationalchickencouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/NCC_CategoriesExplained_Jan2019_Final.pdf Accessed Jan. 29, 2019

Posted on June 13, 2019