Specialists explore new options for managing flock health while defending judicious antibiotic use

Growing demand for poultry raised without any antibiotics has put more pressure on veterinarians to find alternative yet dependable disease-control options, according to a panel of nine experts at a recent roundtable, “Poultry health: New challenges for a new era.”

“We know all veterinarians in the poultry industry are committed to providing optimal care and welfare,” Lloyd Keck, DVM, ACPV, a technical services veterinarian for Zoetis, told Poultry Health Today after moderating the roundtable.

“The goal of this forum was to develop a better understanding of the new health challenges poultry companies face as they try to reduce or eliminate these FDA-approved antibiotics from their health programs.”

Don’t miss a word.

For a FREE copy of the proceedings booklet,

click here.

Although it still accounts for a small fraction of the poultry market, antibiotic-free production is clearly on the upswing as producers respond to increased demand from consumers and large food vendors. according to published reports, dollar sales of poultry raised without antibiotics increased by 25% during the 52 weeks ending January 25, 2015.

Veterinarians on the panel involved with antibiotic-free production cited increases in 7-day mortality as well as total bird mortality. they also expressed concern about the long-term sustainability and welfare implications of raising birds without antibiotics on a large scale, and the potential impact of antibiotic-free production on food safety.

7-day mortality

7-day mortality

At one major antibiotic-free operation, 7-day broiler mortality due to withdrawal of antibiotics in the hatchery increased 0.5% on average, according to Practitioner 1, a veterinarian at a major US poultry company. Prior to that, mortality was consistent with industry averages — less than 1% in the summer, a little more than that in winter and about 0.9% to 1% year-round. Panelists suspect that increased 7-day mortality is due to bacterial disease such as Escherichia coli.

“I have no data to support this, but I would hypothesize that eliminating the use of antibiotics in the hatchery might [also] have longer-term consequences and be associated with problems such as bacterial chondronecrosis with osteomyelitis, septicemia, vertebral osteoarthritis and infectious process,” the veterinarian added. Practitioner 2, who represented another leading US poultry company, reported seeing comparable upswings in 7-day mortality in antibiotic-free flocks: “we run about 1% mortality with antibiotics in the hatchery and about 1.40% without them.”

After 8 weeks on an antibiotic-free program, a veterinarian from the third US poultry company represented on the panel reported seeing only a slight increase in mortality — 0.3% at 7 days — but added that the season might have helped minimize losses. “of course, it was summer, which is normally the best time of the year for 7-day mortality. we’ll see how this coming winter goes,” Practitioner 3 reasoned.

Total flock mortality

According to Practitioner 2, total flock mortality for antibiotic-free production is usually twice as high as it is in commercial flocks that receive FDA-approved antibiotics for disease management. “If you look at 2014 data, antibiotic-free production averaged 10% total mortality, while the average conventional company had 5% total mortality. Antibiotic-free production doubles mortality. It’s killing 100% more chickens,” Practitioner 2 said.

Turkey producers face similar challenges, according to David Rives, DVM, formerly with Prestage farms, a major US turkey producer, and now a technical services veterinarian for Zoetis, which sponsored the roundtable.

“Even on the best-managed farms, it’s very difficult to grow a flock of [antibiotic-free] toms for 20 weeks without facing some disease challenge. Mortality can easily reach twice that of conventionally raised turkeys,” Rives said.

In fact, he added, growing turkeys without antibiotics may be even more challenging than it is with broilers simply because turkeys are in the field longer.

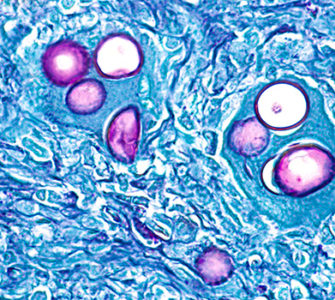

Coccidiosis pressures

The biggest impact of antibiotic-free production has been its adverse effect on gut health, particularly regarding management of coccidiosis, Practitioner 1 said. farms that want to produce birds without antibiotics need to avoid ionophores — which are classified as antibiotics by FDA even though they are used by the poultry industry as antiparasitics to prevent coccidiosis, not to manage bacterial disease.

While coccidiosis vaccines have shown potential in some production schemes, they have not proved to be dependable replacements for ionophores, veterinarians on the panel said. without ionophores, producers must rely on synthetic or chemical anticoccidials, which easily develop resistance, and on vaccines, which have been shown to be less effective in seasons with higher coccidiosis pressure.

“When you go 100% antibiotic-free across the board, it becomes very difficult to use a coccidiosis vaccine effectively [year-round],” Practitioner 1 said, adding that vaccines are usually less effective in the cool, wetter months of fall, winter and spring, when there tends to be more coccidiosis pressure in broiler houses. “In fact, I’ve found it exceedingly difficult [to use a coccidiosis vaccine effectively]. So, you suffer the consequences, which are coccidiosis and secondary infections like necrotic enteritis,” the veterinarian said.

Other complications

Initially, the most obvious impact of enteric disease is reduced growth rate and poor feed conversion, but there are other consequences, Practitioner 1 added.

“Litter condition may suffer, which can affect footpad quality and respiratory health. that becomes an economic and animal-welfare issue.”

Charles Hofacre, DVM, MAM, PhD, university of Georgia, said that coccidiosis vaccines might be suitable replacements for ionophores if they were administered by eye drop to ensure every bird gets a full dose, but that’s impractical when thousands of birds need to be vaccinated.

As things are now, “we don’t have good coccidiosis control in antibiotic-free production, and so Clostridium [a cause of necrotic enteritis] has the opportunity to flourish,” Hofacre added.

Steve Davis, DVM, pointed to studies by his company, Colorado Quality research (CQR), which showed that flocks given ionophores to prevent coccidiosis often had a lower incidence of necrotic enteritis than birds that only received an antibiotic indicated for necrotic enteritis prevention. “that’s because the more you can prevent coccidiosis, the less pressure you’ll have from enteritis,” he explained.

Combatting disease pathogens

Davis expressed concern about antibiotic-free production compromising food safety. “No one’s talked about higher condemnations for antibiotic-free flocks, but it’s been my experience that there are more sick chickens getting to processing age that did not receive antibiotics compared to those that received ionophores,” he reported. “any time you have sicker flocks going into the plant, there’s a greater chance that sick birds will end up in the food chain due to human error.”

Davis said other changes may be necessary as antibiotic-free production gains momentum. “If the trend continues,” Davis said, “we’re going to have to concrete all the floors in our chicken houses. we’re going to have to go heavily with formaldehyde [to kill disease pathogens].”

While formaldehyde is an approved disinfectant for poultry houses, two of the panelists said some consumers might find it more objectionable than using animal antibiotics to prevent common poultry diseases.

“In addition, we’re going to have to better control the humidity of our chicken houses,” Davis added. “We’re not going to be able to use cool-cell pads; we’re going to have to go to air conditioning, because you’re going to have to have a dry environment in those chicken houses if there’s any chance of remaining sustainable without in-feed ionophores or antibiotics in the water.’’

Practitioner 3 said scaling back on bird density might lessen the incidence of necrotic enteritis, but it would have to be done “dramatically” to have an impact. Lower bird density would lead to higher production costs per bird, which would be passed on to consumers.

Antibiotic alternatives

When moderator Keck asked if healthy gut microflora could be maintained with alternatives to antibiotics, the panelists acknowledged their potential but said switching was easier said than done.

“We’re finding that two [alternative] products can look identical on paper, yet one can be very efficacious in our necrotic enteritis model; the other one is not only ineffective, but makes necrotic enteritis worse in terms of lesion scores and/or mortality,” CQR’s Davis said. “We’re probably dealing with issues of consistency.”

He cautioned that when producers opt to use non-drug replacements, they quickly discover there’s a fine line between what works and what doesn’t. “It might vary from batch to batch and you might see good results or you might make the situation worse. this is something we’ve found quite surprising in our research,” Davis said.

With the growing demand for poultry raised without antibiotics, Practitioner 1 observed that treatment alternatives were “coming out of the woodwork” and compared the situation to “the wild west” because these additives are not subjected to the same regulatory scrutiny as antibiotics. For example, organic acids, probiotics and pathogen-associated molecular-pattern products are not drugs by definition and do not have to be submitted for FDA approval.

‘Real conundrum’

Most of the companies selling these alternatives provide pen-trial data to show their efficacy, but testing these products in real-world situations has been a real

conundrum, Practitioner 1 continued. “Based on the few thorough trials I’ve been able to do, I’ve not found one of these products yet that I’m using in antibiotic-free production.”

Practitioner 3 echoed similar experience. “We’ve tried several of these [alternative] products, and we still had a lot of necrotic enteritis in our birds raised without antibiotics.”

On a brighter note, Rives said some direct-fed microbials, yeast cell-wall products and saponins had shown some promise in young turkeys. Effective prevention and control of protozoa other than coccidia may be the bigger challenge with turkeys.

Gut health is critical for turkeys just as it is in broilers, the turkey veterinarian emphasized. “There are other substances that can mimic performance antibiotics, and it’s going to require the right combination of probiotics, prebiotics and other alternatives to maintain optimal microflora in the gut at each stage of growth. this is especially critical for turkeys in the brooder house.”

Tall order

Dennis wages, DVM, ACPV — a professor at North Carolina State University focused on disease prevention — acknowledged that maintaining intestinal health in poultry flocks while meeting demand for birds raised without antibiotics was a tall order for producers.

“The challenge for the US poultry industry will be to effectively control gut populations [of pathogens] in other ways, either through immunomodulation or with some of the natural products or with vaccines,” Wages said.

Georgia’s Hofacre noted that experience with antibiotic alternatives might improve as [US] producers gain more experience with them in different housing systems or times of year.

“No matter what’s thrown at it, the poultry industry always seems to find a way to solve these problems,” he said. “There are lots of alternatives to antibiotics that we may find don’t work as well as antibiotics, but they might prevent antibiotic-free birds from suffering and having 100% greater mortality.”

Regulatory wish list

The simplest and most effective way to control gut disease, reduce mortality and improve welfare in antibiotic-free production would be to adopt Europe’s approach and classify ionophores as antiparasitics, not antibiotics, the panel said. “It would be the holy grail for the [US] poultry industry if we could have ionophores reclassified, but today one of our biggest challenges is on meat labeling,” said Ashley Peterson, PhD, vice president of science and technology, National Chicken Council.

“As it is now, you either do or you don’t use antibiotics — and there’s not a lot of gray area because consumers may not understand the importance of ionophores in poultry production and how they do not lead to resistance [in humans].”

Although Peterson sees opportunities for discussions with FDA about this issue, she could not predict if the agency would be receptive. “It would help if we could get some consumer groups to join in,” she said.

It’s her impression that FDA is convinced antibiotic use in food animals is “rampant” and that there’s a definite link between human resistance and antibiotic use in livestock.

‘Judicious use’ label?

Practitioner 2 said that while preserving antibiotics for human medicine was paramount, consumers and producers needed to find middle ground to ensure the health and welfare of poultry and livestock under veterinarians’ care.

“This all-or-nothing approach [to antibiotic management] is not sustainable, and the data say it’s pretty onerous for the chickens. It’s double mortality.”

One solution might be a “judicious use” label from the USDA Food Safety and Inspection Service — something to assure consumers that antibiotics were used properly and under veterinary supervision to ensure flock health and welfare — that could be put on the package if specific guidelines for antibiotic management were followed by producers, Practitioner 2 suggested.

For more articles from this special report on managing flock health, click on the titles below:

Marketing vs. Medicine: Finding the balance

Posted on March 27, 2016