Poultry companies using variety of interventions to improve food safety

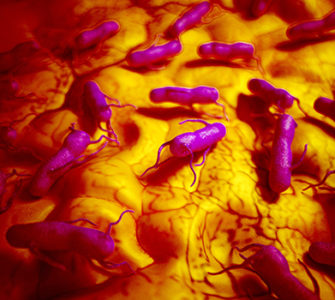

Poultry companies are using a variety of interventions to curb Salmonella and improve food safety, even though it’s not always easy to justify the cost of each, panelists said at a food-safety roundtable.

“Dry litter is huge,” said John Smith, DVM, president, Alectryon LLC, formerly with Fieldale Farms.

Litter amendments such as acidifying agents not only reduce Salmonella but also have other benefits, such as ammonia control, that clearly justify their use, so that’s a win-win and consequently an easy sale in live production, he said.

Bruce Stewart-Brown, DVM, senior vice president, technical services and innovation, Perdue Farms, agreed that dry litter is a “double win.” There’s less ammonia and better respiratory health as well as less Salmonella, he said at the roundtable “Coming Together for Food Safety.”

Footpad health as indicator

Dry litter also contributes to good footpad health, he said. “If there’s a No. 1 indicator for live-side food safety, it might be footpad health because really good feet generally mean there’s really good litter and fewer microorganisms in the chicken house,” Stewart-Brown said.

Double wins in live production that are easy to justify are typically food-safety interventions that can operate every day, all the time, and “you can hold live production accountable for as well,” he said.

Robert O’Connor, DVM, senior vice president, technical services, Foster Farms, added, “Wet litter time and time again will drive up your Salmonella…I’ve seen it and it doesn’t matter whether it’s broilers in Louisiana or California or breeders in Colorado. Wet litter definitely has an effect on the prevalence of Salmonella all the way through to the plant.”

Look to soiled-feather scores

Look to soiled-feather scores

Stewart-Brown said soiled-feather scores are another useful metric. “If you’ve got some farms that are typically dirty-feather farms, figure out what that’s about and bring them in cleaner.

“If you can reduce the amount of organic material being brought to the plant each day, the plant’s operational interventions for Salmonella control will work better.”

Smith added that competitive exclusion, good coccidiosis control and maintaining good gut health in general all contribute to Salmonella control and provide other economic benefits to the live side that make them easy interventions to promote.

Live Salmonella vaccines, he noted, can have a rapid impact on Salmonella in the broiler house. However, due to their expense and because they may not have economic benefits directly to the live side of poultry production, they tend to be reserved for use when a complex finds itself in USDA’s Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) Category 3.

Water acidification

Douglas Fulnechek, DVM, senior public health veterinarian, Zoetis, and formerly a supervisory veterinary medical officer, FSIS, said water acidification is another strategy used by some companies to combat Salmonella.

He advised lowering the water pH from 48 to 72 hours before processing.

“You need to lower it to the lowest level that does not affect water consumption. That’s somewhere around a pH of 4 and, depending on the water system, there are some companies that can get it below 4,” he said.

“On very well-managed broiler farms, growers titrate the pH; they might even do that over a period of 5 days so they can get it lower without affecting water consumption.”

Cost justification

Charles Hofacre, DVM, PhD, round table moderator and president, Southern Poultry Research Group Inc., asked if anyone has figured out if spending more money for Salmonella control during live production reduces costs at the processing plant and if any companies have even had that discussion.

Erin Johnson, director of food safety, George’s Poultry, said, “I think that the discussion comes up frequently. I am just not sure that we have found the balance.”

Carl Heeder, DVM, senior director, live operations, Mountaire Farms, said at his company, the question comes up at least once a year during budgeting when expenditures for peracetic acid (PAA) are realized.

Live production asks how much of a reduction in Salmonella is needed before the plant could stop using PAA — but there isn’t an answer, he noted.

Fulnechek said Zoetis has at least one customer focusing on Salmonella intervention efforts on the live side, and they have very little cost for interventions in the plant other than some at first processing. They use all the tools available, including testing and vaccination against Salmonella, and they’re being successful.

“They have no interventions in second processing, and they are in FSIS Category 1 for carcasses and parts. They don’t have a comminuted product, so I can’t judge how well this approach would work there,” he said.

Going this route, however, requires a high-functioning, well-coordinated and committed team. Everyone has a critical role, Fulnechek continued.

Since Salmonella does not originate at the processing plant, its mitigation has to begin with the pullet chick, he said.

“You must have the immune system’s help in addition to all the other management tools. The goal is for the hen to pass Salmonella immunity, as opposed to Salmonella, to the broiler chick. That makes immunization/vaccination critical.”

The primary goal is to minimize Salmonella exposure and passively protect the broiler chick during its first 14 days of life. But the broiler chick can also be vaccinated to stimulate active immunity and to minimize late shedding and load carriage into the plant, Fulnechek said.

“Vaccination can be regarded as a way to protect the broiler chick from the inside out,” he added.

Read the rest of this article and download our “Coming Together for Food Safety” special report.

Posted on June 9, 2021