Maslow’s Pyramid: Self-actualization for chickens?

By Philip A. Stayer, DVM, MS, ACPV

Corporate Veterinarian

Sanderson Farms, Inc.

What makes a chicken happy? And why consider a chicken’s happiness? As poultry veterinarians, we continually strive to improve the welfare of animals to help them reach their full potential. It would seem to reason that chickens with good welfare are more likely to be “happy” — and be more productive.

It occurred to me an interesting exercise would be to apply Maslow’s pyramid to chickens. Abraham Maslow is a psychologist who, back in 1943, came up with a universal hierarchy of needs, often illustrated in pyramid form. The first and most basic need, according to Maslow, is physiological. At the top of the hierarchy is self-actualization — when fulfillment enables a person to be at his or her very best.

How can we apply Maslow’s pyramid to chickens? What would be the hierarchy of needs for chickens to ultimately reach “self-actualization”? What follows are the cumulative observations and speculations of an experienced, mature (though some may say “old”) poultry veterinarian.

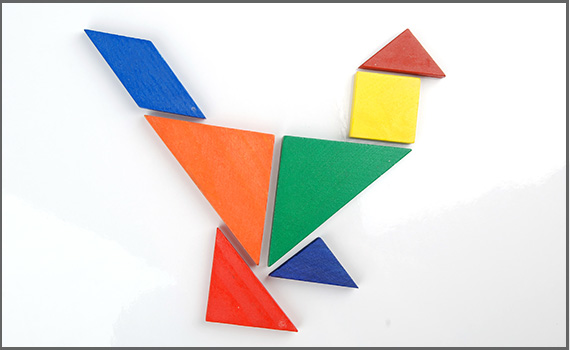

Figure 1. Maslow’s pyramid and the pyramid applied to chickens

Apart from oxygen — an essential key physiological need for any aerobic species — I would assign four “freedoms” chickens need to reach self-actualization, which are akin to the often quoted “Five Freedoms” of animal welfare.

The safe, comfortable chicken

The first tier in the hierarchy of needs would be protection from predation. This is an instinct that’s easily observed in commercial poultry. If you wave a solid object over their heads or shine a light overhead when it’s dark, chickens will immediately squawk and run away from the offending stimulus, which they presumably interpret as a flying predator like a hawk or owl. Keeping chickens inside a structure with a roof resembles the protective canopy of an Asian rain forest, from where they originated.

Thermal comfort would be next in the hierarchy of needs for chickens and is most likely more important to chickens than food or water. This is really apparent in day-old chicks. If they’re either cold or hot, they won’t eat or drink.

Since we raise chickens far away from their ancestral Asian home, their thermal comfort must be addressed with man-made means. In the US, we raise “biddies” in brooding environments to warm baby chicks in the winter and cool them during brutally hot summer months. Free-range chicks may suffer from temperature extremes if their need for thermal comfort is ignored.

Third on the chicken’s journey to contentedness are food and water. Chickens are omnivores, and meeting their nutritional needs is most easily achieved with a combination of grains and animal proteins. Water availability and good water quality are vital. Water must be potable and free of pathogens for poultry to flourish.

The social chicken

The next level in the hierarchy of needs for chickens that corresponds with Maslow’s self-actualization level might be termed “frolic,” and it encompasses the social aspects of being a chicken. Chickens are social animals — that is, they live in flocks — and they like to be among “birds of a feather.” In brief, chickens appear less agitated when surrounded by other chickens.

This was never more apparent to me than when another veterinarian and I were trying to figure out the most gentle way to handle birds going to processing. Together we caught an entire transport coop of chickens (about 150 individuals) by ourselves, with one chicken per hand. We loaded the transport module, transported the coop to the processing plant, unloaded and individually surveyed each one of the chickens.

We noticed birds flapped their wings more when we each had one bird in hand, whereas the contract catchers had multiple birds per hand. If we picked up chickens as pairs, two in each hand, flapping decreased. The chickens appeared to receive comfort from other chickens in near proximity.

Another clear example of chickens’ social behavior occurred after Hurricane Katrina in 2005. Sanderson Farms lost over 70 chicken houses on contract farms. In many cases, all that was left were the floor pads. Walls and roofs were gone. This was in late August in south Mississippi and it was stinking hot. Broilers scattered and wandered into the cool shade of the surrounding woods during the day, but every night, they would return to the floor pads where their houses once stood to spend the night in the company of flockmates.

Protecting chickens from themselves

Some social behaviors among chickens are unacceptable, just as they are among humans, and they have to be managed by caretakers to protect chickens from themselves.

One example is the “pecking order,” a natural behavior that emerges as members of a flock discover where they belong in their social strata. Breeder chickens’ beaks are treated so their primary “bullying” weapon is dulled to prevent them from dismembering other birds.

Enhancements have been proposed, like shiny objects that arouse curiosity and entice chickens to take the object from one another, but that can encourage chickens to run around and result in injuries. In modern poultry houses, caretakers use subdued lighting to keep chickens calmer and discourage crowd chaos. They may also use migration fences to prevent chicken pile-ups at one end of the house. These measures might be compared to requiring kids to wear bicycle helmets for their own protection instead of allowing them free rein to express all their “natural behaviors.”

I don’t know if reining in natural behavior interferes with the chicken’s self-actualization, but in my experience, chickens are happy to eat, drink and be merry in the modern poultry house. They’re probably a lot happier if they aren’t pecked to death by flockmates and are protected from injuries suffered in a high-speed pile-up.

Have we built the case for the “self-actualized chicken”? What we humans may like does not mean that is what chickens may prefer. Exactly how chickens can ultimately achieve “self-actualization” may or may not eventually be elucidated by research.

In the meantime, the best approach I’ve found comes from fellow Mississippian Tim Cummings, DVM. When he taught at Mississippi State University, his advice was “Listen to the chickens.” I would venture to say that Tim also meant “observe.” Listening to and observing chickens will tell us more about what makes a chicken happy than trying to anthropomorphize our desires onto chickens.

Editor’s note: The opinions and advice presented in this article belong to the author and, as such, are presented here as points of view, not specific recommendations by Poultry Health Today.

Posted on June 17, 2019