The link between Salmonella and intestinal health

By Charles L. Hofacre, DVM, MAM, PhD

President, Southern Poultry Research Group, Inc.

Professor Emeritus, University of Georgia

Changing consumer preferences in many areas of the world are pressuring poultry producers to reduce or eliminate routine use of antibiotics. The result has been an increase in intestinal disease.

In a recent US survey, veterinarians reported a significant increase in the number of broiler flocks that are experiencing intestinal disease associated with a higher incidence of coccidiosis. At the same time, the public health community has been exerting considerable pressure on producers to lower the level of pathogens such as Salmonella spp. that can cause foodborne illness in humans if present on raw poultry meat and in table eggs.

These trends underscore the need for an even better understanding of the chicken’s intestines, its complex ecosystem and its intricate inner workings.

Normal flora

For decades, the scientific community has tended to view the intestines of the chicken and its normal flora as individual units. We’ve analyzed the enzymes, digestive acids or gut villi necessary for digestion, scrutinized intestinal bacteria and studied coccidia and its ramifications.

This approach has been extremely valuable in understanding the role that intestinal health plays regarding bird health. Back in the 1970s, for example, it was shown that “normal” cecal flora bacteria from a healthy hen could prevent a newly hatched chick from being colonized by Salmonella infantis. What wasn’t recognized, however, was the effect that feed ingredients could have on the ability of the bird’s intestinal bacteria flora to colonize. Also, little was known about the full impact of coccidia, as well as which bacteria are “good guys” or “bad guys.”

We now know that Salmonella spp. is part of the normal flora of healthy chickens. We also know that Clostridium perfringens and its close family are a major part of the normal cecal flora of healthy broilers, but when given the opportunity by coccidial infection, the toxin-producing strains of this pathogen will grow to high numbers in the small intestines of broilers, leading to necrotic enteritis and resulting in poor growth, lost feed efficiency or death.

The normal bacterial flora of broilers fed a corn- and soybean meal-based diet is very different in the small intestine compared to the ceca. In these birds, the bacterial flora of the small intestine, analyzed by 16 SrRNA gene sequences, is nearly 70% Lactobacillus spp. (lactic acid bacteria) and 10% Clostridiaceae (the family of Clostridia that includes Clostridium and related bacteria). In contrast, the ceca is nearly 70% Clostridiaceae and just under 10% Lactobacillus spp. This normal flora has also been shown to be significantly affected by feed ingredients — wheat versus corn-soy based — as well as by ionophore anticoccidials or even the quality of the feed ingredients, such as rancid fat or mycotoxins.

It’s important to keep in mind that the ceca (Figure 1) is the source for many of the normal bacterial flora of the small intestine due to retroperistalsis of the intestines. This reverse movement of cecal contents up into the small intestines occurs on a frequent basis, which makes good cecal health important to the overall health of the bird’s intestines.

Figure 1. Scanning of colorized ceca of chicks before (top) and after developing normal bacterial flora

(bottom)

Coccidia

The protozoan parasite Eimeria spp. can be found in every commercial poultry house. Different pathogenic species of Eimeria infect different locations in the intestine of the bird and result in either reduced growth or death.

In broilers, Eimeria maxima can wield major insults. It damages epithelial cells in the small intestines, increases cytokine production, then mucus-producing goblet cells and, consequently, increases growth of the mucolytic bacterium Clostridium perfringens, which ultimately results in necrotic enteritis.

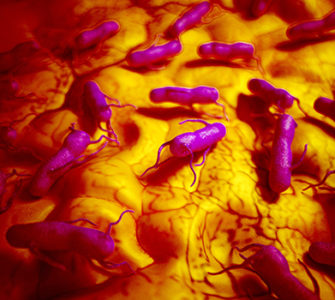

E. tenella can cause higher colonization of Salmonella in the ceca by damaging epithelial cells, resulting in increased cecal colonization of Salmonella typhimurium (Figure 2) and a greater risk that Salmonella will be translocated into the liver and spleen of the chicken.

Figure 2. Colorized scanning electron micrograph of Salmonella typhimurium grown in a pure culture

Source: CDC/Bette Jensen [public domain photo]

Intestinal disease and Salmonella

Are intestinal disease and Salmonella linked? The answer is “sometimes,” as shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Intestinal disease effect on gut flora and Salmonella

|

Treatment |

Cecalcoccidiosis score |

Necrotic enteritis mortality |

Salmonella in environment (drag swabs at 42 days) |

Salmonella in ceca (42 days) |

| Salmonella only |

0.2 |

0% | 67% |

67% |

| Necrotic enteritis only |

0.5 |

38% | 33% |

7% |

| E. tenella prevention |

0 |

21% | 0% |

0% |

| Necrotic enteritis prevention |

0.2 |

16% | 33% |

13% |

| E. tenella and necrotic enteritis prevention |

0.1 |

12% | 0% |

0% |

Hofacre, 2007, J Appl Poult Res.

Broilers that are 42 days old with a severe case of necrotic enteritis do not always have a higher prevalence of Salmonella heidelberg. However, research has shown that while necrotic enteritis does not necessarily result in higher Salmonella colonization, increased intestinal disease due to E. tenella in the ceca can. When E. tenella is controlled, S. heidelberg colonization is significantly less.

Exactly how E. tenella causes increased Salmonella colonization is not completely understood. Our research has shown, however, that it can be affected by the methods we use to control E. tenella. The prevalence of Salmonella in broilers vaccinated with a coccidiosis vaccine was 17% lower than in non-coccidia-vaccinated control birds and 16% lower than in ionophore-treated broilers.

It could be theorized that the lower coccidia dose in the vaccine resulted in a rapid immune response to E. tenella early in the broiler’s life, and that by market age, Salmonella was reduced. Another explanation may be that a rapid host inflammatory response in the ceca makes it more difficult for the Salmonella to colonize.

In summary, the chicken’s intestine is a complex organ that is a balance of bacteria, viruses and protozoa. When a condition such as coccidiosis occurs that alters this delicate balance, then the normal bacteria flora is adversely affected.

Salmonella is a small but normal part of the bacterial flora of a healthy chicken’s intestine. To prevent it from becoming a larger part of the normal cecal flora, it’s critical that all segments of intestinal flora be managed.

We are only beginning to understand the complex ecosystem of the chicken’s intestine, but as we increase our knowledge, we will be better able to minimize intestinal disease and have a broiler that grows more efficiently while also providing wholesome and safer food for consumers.

Editor’s note: The opinions and advice presented in this article belong to the author and, as such, are presented here as points of view, not specific recommendations by Poultry Health Today.

Posted on June 26, 2018