Shrewd moves: Like a chess match, anticoccidial rotation is a game of strategy at Wayne Farms

Rotating anticoccidials is a lot like playing chess, says Mark Burleson, DVM, head veterinarian at Wayne Farms. Your next move might address an immediate need, but it also could determine what pieces are still standing later in the match. It is, after all, a game of strategy.

On paper, Burleson says, it appears that poultry companies have a smorgasbord of options — more than a dozen antimicrobials and six vaccines in the US alone — for managing the costly disease, which in its subclinical form can take a huge bite out of feed conversion and growth rate. But in reality, the menu is pretty sparse, he says.

“The chemicals can be used only one cycle at a time with lots of rest time in between, so that cuts your options in half right there,” the poultry veterinarian says. “The ionophores can be used longer, but they have their limitations, too.

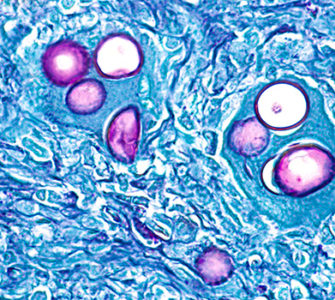

“One product can’t be used if you’re exporting to China, for example. Another one can’t be used in the summer. Still, another product is not very good on Eimeria maxima, which is your big feed-conversion killer. So, when you take all those factors into account and consider that some products do better at different stages of the growth cycle, it starts bringing down the number of options pretty quickly.”

‘Tools in the shed’

Vaccinating for coccidiosis is a good option for some operations, but getting good vaccine uptake — and thereby ensuring good performance — is sometimes a challenge. For some operations, supplementing the vaccine with a low level of an ionophore after vaccinal oocysts are done cycling is one option for providing added protection and thereby optimizing bird performance.

Whether using chemicals, ionophores, vaccines or a combination of all three, the best solution is to plan long term, Burleson says. “We have a lot of tools in the shed, but they’re not all available at the same time or for the same job. And remember, most are antimicrobials, so resistance develops. You have to rotate them properly to keep them effective.”

Burleson says he plans his coccidiosis-management strategy at least 12 months in advance on paper and even longer in his head. He has a strict rule about never using the same in-feed medication for more than two cycles in Wayne’s larger birds, fed to 63 days, and up to three cycles for birds grown to 40 days.

“I try to be proactive and not wait for leakage to occur before I switch products,” Burleson says. “I feel like that’s the best way to make your products sustainable and be available for use year after year.”

Knowing when to jump

Chad Robertson, a grower for Wayne Farms who manages four houses with 68,000 broilers at his farm in Arab, Ala., agrees with Burleson’s long-term, judicious approach to coccidiosis management.

“You definitely need to stay with a program and not be jumping around too much,” he says. “You also can get into trouble when you try to push the envelope on a program. It’s very tempting to ride the train too long before it gets to the station, when in hindsight you should have jumped off.”

Robertson says his farm’s daily weight gain has increased 15 points over the past two grow-outs by focusing more on anticoccidial-rotation patterns, as well as paying more attention to lighting over the feed pans and sanitizing the drinking-water lines. “I also like to run vinegar or citric acid at certain ages in the grow-out to try to keep the gut in check,” he says.

Coccidiosis calendar

Wayne Farms’ coccidiosis-management calendar begins in October, when houses are closed up more to conserve heat, thereby increasing chances for wet litter and more coccidiosis pressure.

Burleson kicks off the season with nicarbazin in the starter, sometimes feeding it for as long as 28 days in the colder months but always finishing the birds with one of the ionophores — lasalocid, monensin, narasin or salinomycin.

The chemical-ionophore shuttle continues until March, when Burleson switches to what he calls his “spring clean-up” with an all-chemical program from start to finish. This past spring, for example, he used decoquinate.

“There’s really good performance associated with knocking down the coccidiosis load with a chemical,” he says. “Gangrenous dermatitis really picks up in the spring. So the more you can knock back coccidiosis, the less dermatitis you’re likely to see.”

Two options

Following the spring clean-up, Burleson has two options. He either rotates to a vaccine — usually Inovocox EM-1, which is administered in ovo at the hatchery — or he goes with a carefully orchestrated rotation of ionophores. He takes care not to rotate from one monovalent ionophore (monensin, narasin, salinomycin) to another so that Eimeria organisms are exposed to an anticoccidial from another molecular family. That could be a chemical or the divalent ionophore lasalocid.

While anticoccidial rotation is standard practice on all commercial poultry farms, Burleson calls it “one of the struggles of the industry.”

He adds, “We need to be smarter about it. We like to use products when they’re performing well, obviously, but too often we keep using them until they don’t work anymore.

“For us, after years of using monensin, narasin and salinomycin, we felt like we needed a change of pace on the ionophore side,” he continues. “Over the past 2 years, we’ve used a lot of lasalocid and it’s performed very well for us.”

The veterinarian is quick to credit Wayne’s head nutritionist, Tom Frost, PhD, who recommended changing the electrolyte levels in the feed with lasalocid to avoid wet litter. “So we’ll use, say, salinomycin in the starter and then rotate to lasalocid,” Burleson says.

Preventing burnout

To prevent product burnout, Burleson keeps a close eye on bird performance, as well as the results of posting sessions conducted every 6 to 8 weeks. But even then, diagnostics only provide a snapshot.

“For instance, if I’m at a posting session and see heavy cycling between 28 and 32 days — and typically, we include only two flocks in that age range at a posting session — I’m then going to the field to look at more flocks in that age range and see if those two flocks were representative of the whole complex,” he says.

Litter management also affects the success of a coccidiosis program. Between cycles, Wayne Farms has had good results windrow-composting the litter. It heats up litter to around 130° F, which kills Eimeria oocysts and other pathogens. “If you can manage that litter properly and bake out the pathogen load, you’ll be much better off with your coccidiosis management program and make the products more sustainable,” he says.

“As a production veterinarian, my goal is to be sustainable and to raise a healthy chicken. From an animal-welfare standpoint, I try to give our chickens all I can to make sure they’re happy and healthy while they’re under my watch. Antibiotics, when used judiciously to manage disease, help us to be more efficient, productive and sustainable.”

Posted on April 29, 2015