Five opportunities to optimize gut health, minimize necrotic enteritis in broilers

By Suzanne Dougherty, DVM, MAM, MS, DACPV

Pecking Around Consulting, Inc.

Madison, Ala.

Intestinal health has become more of a challenge during broiler growout than ever before. One of the most common intestinal diseases in both conventional flocks and flocks raised without antibiotics is necrotic enteritis (NE), caused by an overgrowth of the bacterium Clostridium perfringens.

Compared to conventional poultry-management programs, those that prohibit drugs classified as antibiotics, including ionophores, are more likely to experience NE and other intestinal health issues.

Conventional flocks, however, can experience NE if resistance to an ionophore develops, leading to coccidiosis that damages the intestinal tract. The damage sets up the perfect environment for clostridial growth and can lead to NE. NE might occur in a conventional flock if a synthetic anticoccidial (a non-ionophore drug) is used without an antimicrobial along with it. The anticoccidial may control coccidia, but if there’s nothing used to control bacteria, Clostridium can overgrow, causing NE.

Any type of flock vaccinated against coccidiosis can experience NE if the vaccine isn’t properly applied or managed in the field. Enhanced coccidial cycling can also set up a favorable environment for Clostridium growth.

One of the most important components for preventing NE in all types of broiler flocks is good intestinal health, which is influenced by many factors including chick quality, brooding, feed and farm management and, particularly, coccidiosis. To achieve healthy intestines and prevent NE, especially in flocks raised without antibiotics, attention to detail in each of these areas is critical and can often be achieved by getting back to basics.

Chick quality

Optimal chick quality is vital and begins with the intestinal health of the pullet and hen. The way we currently feed — skip a day for pullets and daily, short-feed cleanup times for hens — can have a negative impact on beneficial intestinal microflora, including Lactobacillus- and Bacillus-type bacteria, in the breeder and broiler. These adverse effects in broiler chicks can be minimized with the use of probiotics in water or spray at the hatchery or with prebiotics in the feed to help establish and maintain better microflora.

Chicks need to be exposed to “good bacteria” during hatch, which requires a clean egg pack and hatchery, especially when hatchery antibiotics are removed. Some companies growing flocks without antibiotics are spraying either a competitive-exclusion or probiotic product at the hatchery to try and seed the intestines with good bacteria.

The bacteria that make up a chick’s intestinal microflora are usually comprised of the bacteria the chick is exposed to in the first few days of life. Good bacteria applied on day 1 of age are more likely to colonize than unwanted bacteria such as Salmonella or Escherichia coli. Products containing desirable bacteria can also be given in drinking water.

Stress on birds needs to be minimized in all types of broiler flocks. Overheating during incubation, hatching or transportation negatively affects maturation and development of the intestinal tract and, in turn, impairs nutrient absorption, feed conversion and bodyweight gain. Overheated chicks are typically tired and lethargic when they arrive on the farm. They’re the chicks that don’t get up and move to feed and water within the first few hours of placement.

Evaluating the hatch of flocks 12 hours before chicks are scheduled for processing is an excellent way to ensure there is minimal stress imposed on birds. Monitoring the percentage of chicks hatched out 12 hours before pull can help determine the potential for overheating and dehydration. I advise checking chick rectal temperatures throughout the process. Chick temperatures can provide valuable information about hatching and delivery methods and need to be maintained at an acceptable range before farm placement.

Make sure your transportation vehicles have proper airflow and that chicks don’t get overheated or chilled on the way to the farm. This can happen quickly, resulting in damage that could last the life of the flock.

Brooding

Optimal brooding conditions the first 7 to 10 days can go a long way toward raising a healthy flock and minimize the chance they’ll develop NE later.

Chicks need appropriate floor temperatures and good air quality with low ammonia. Treat each house as one flock because some flocks need a warmer floor than others, which can be due to the breeder flock’s source age. Look at your chicks and they’ll indicate if they’re too hot or cold by the way they spread out or congregate in the house.

Giving chicks access to feed and water within 24 hours of hatch can benefit intestinal health and reduce the chances of NE. Feed stimulates the intestinal tract and encourages its maturation. Supplemental feeders or feed pans should be easily accessible at placement and during brooding. I like to see supplemental feeders in place for at least 7 days in flocks raised without antibiotics.

Many companies, particularly those raising broilers without antibiotics, are acidifying (3.5-6 pH) the drinking water continuously the first 7-10 days. This supports good bacterial colonization in the intestines while reducing the likelihood of unwanted bacteria like Clostridia.

Feed

A healthy intestinal tract requires consistent, high-quality feed ingredients and consistent feed form. Avoid switching from crumbled to pelleted feed, for instance, or switching from feed that’s 70% fines one delivery and 30% fines the next. These kinds of changes can adversely affect intestinal absorption and lead to disease issues. Feed ingredients need to be consistent as well to avoid disrupting the chick’s intestinal microflora.

Any changes in feed are difficult for flocks, including the transition from starter to grower feed. To minimize intestinal tract disruption, it helps to acidify the water 2 to 3 days prior and for 2 to 3 days after this feed change.

It should go without saying that high-quality feed ingredients without bacterial contamination are necessary to grow healthy broilers. Feed that contains animal byproducts could potentially be contaminated with either Clostridia bacteria or spores. For this reason, many programs not using antibiotics have opted to feed a vegetable diet free of all animal protein, which is proving to be critical for preventing NE.

Birds should have feed at all times, so keep a close eye on feeder lines and pans. Feed outages, even for a short time, can disturb intestinal integrity and induce eating litter, which is full of unwanted bacteria. Many companies are using non-starch polysaccharide enzymes and prebiotics to help maintain healthy intestines. This has proven to be very beneficial for minimizing and preventing NE in flocks raised without antibiotics.

Coccidiosis

Managing coccidiosis is key to preventing NE in broiler flocks raised in all types of programs. NE can occur independently of coccidiosis, but the two typically occur together.

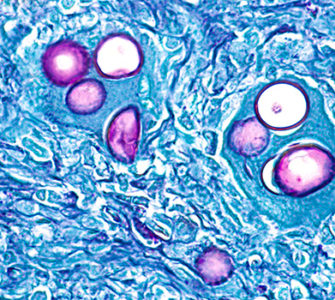

Of the various Eimeria species that cause coccidiosis, damage the intestines and alter the natural intestinal environment, E. maxima is probably the biggest contributor.

When the intestinal tract is disrupted, clostridial bacteria grow and retrograde (move back) from the ceca, where Clostridia normally live, to the middle intestine. It’s the overgrowth or retrograde of Clostridia in the middle intestine that can lead to NE. Again, this scenario is more likely in flocks that aren’t receiving an antimicrobial, such as an ionophore or antibiotic growth promoter to help keep the intestines healthy, but it can occur in conventionally raised flocks as well.

Routinely monitor flocks for evidence of coccidia because the results could indicate that your coccidiosis-management program needs to be changed. There must be a long-term, strategic program that typically includes rotation of anticoccidial products and/or coccidiosis vaccination.

Between-flock house management

Optimal farm-out time between flocks is about 14 to 18 days and is essential for flocks placed during the fall and winter seasons. Coccidiosis is more often a problem during cooler weather and when there are large temperature fluctuations between day and night. This is because broiler houses are closed, usually having less air flow turnover, and there’s more moisture in the litter.

NE prevention measures, however, need to start as soon as the last flock leaves the poultry house. These should include litter and water management, as well as control of rodents and insects such as darkling beetles.

I recommend focusing on litter management within an hour or two after a flock leaves the house. The pathogen load on built-up litter can be reduced by in-house litter windrowing, and, if done properly and while the litter is still hot from the last flock, you can kill many unwanted bacteria and even some viruses. Heating houses will accelerate this process.

During farm-out time and before new chicks are placed in a house, flush all water lines, which can harbor a variety of bacteria, and disinfect. Test your water source annually to determine the pH and check for coliform bacteria such as E. coli, particularly if water is sourced from a well or spring.

In addition to litter and water sanitation, rodent and insect control must be initiated within a few hours after the previous flock leaves the house. These pests can harbor disease. Rodents and insects will leave the houses quickly after birds are gone because there’s no feed to eat, and the houses and litter are no longer warm. Darkling beetles will typically move to the sidewalls, and rodents will go elsewhere to find another food source. If you wait to treat for 2 or 3 days after the birds vacate, there’s a good chance the insects and rodents have left as well — but they’ll be back when the next flock arrives. That’s why your rodent and insect control will be more effective if you treat for them within hours after birds leave a house.

In conclusion, the No. 1 key to controlling NE is control of coccidiosis, but chick quality, optimal intestinal integrity, high-quality feed and careful attention to basic flock and farm management are important too. If you control all these factors, you’ll be on your way to achieving optimal bird health and will greatly reduce the risk for NE, a potentially devastating and costly intestinal disease.

Posted on May 16, 2016