Poultry veterinarian shares ideas for managing coccidiosis more effectively, economically, sustainably

Zoetis recently introduced a new science-based, global initiative to help poultry producers develop longer term, sustainable strategies for managing coccidiosis — a parasitic disease that, according to a 2006 estimate by the US Department of Agriculture, costs the global poultry industry more than $3 billion a year.1 Losses in the US alone are estimated to be more than $600 million annually.2

Called Rotecc™ Coccidiosis Management, the program is reportedly based on decades of published research, pen and field trials and practical experience that Zoetis scientists have gained from helping producers in more than 60 countries manage the disease. Its scope includes all field-demonstrated, in-feed and biological anticoccidial tools available in the animal health industry, not just those developed by Zoetis.

Poultry Health Today recently talked with Don Waldrip, DVM, Dipl. ACPV, senior technical services veterinarian at Zoetis, to learn to learn more about the program and the “best practices” behind it.

How does Rotecc Coccidiosis Management work?

DW: Rotecc begins with a consultation by a Zoetis representative, who reviews past and current programs, necropsy data and results from anticoccidial sensitivity testing, as well as the farm’s seasonal preferences for product usage, production goals and management practices. Other variables such as feed costs and meat prices also are considered.

Drawing on best practices for coccidiosis control widely accepted by the poultry science community, Zoetis representatives work with producers to build strategic, long-term coccidiosis-management plans designed to maximize effectiveness.

To facilitate this process, Zoetis is developing proprietary digital tools to help producers build 12- to 24-month coccidiosis-management plans designed to meet their individual needs and goals.

In the US, for example, Zoetis representatives will soon be armed with the Rotecc™ Program Advisor, an iPad app to help poultry veterinarians, nutritionists and production managers weigh various control programs. The company is also developing a Rotecc™ Calculator for the iPad and Windows operating systems to help guide coccidiosis decision-making.

Specifically, what “best practices” does Rotecc promote?

DW: Rotecc advocates four basic principles for restoring and preserving the sensitivity of coccidia to in-feed anticoccidials.

- Don’t use the same in-feed anticoccidial for extended periods.

- Rotate among different classes of products.

- Rest each product periodically.

- Use a synthetic anticoccidial once yearly to clean up field strains.

- Consider vaccinating periodically to rest all feed products and restore sensitivity.

Why is it necessary to rotate and rest anticoccidials?

DW: Traditionally, commercial poultry operations have used two types of in-feed anticoccidials — ionophore antibiotics and synthetic compounds or chemicals.

All of these products have been demonstrated to be highly effective controlling the coccidial organisms that cause coccidiosis. However, like many therapeutics used in animal or human medicine, some in-feed anticoccidials have lost their efficacy with prolonged administration.

For that reason, rotating anticoccidials — that is, switching the type used after one or more production cycles — or “shuttling” products, which involves changing anticoccidials within a production cycle (e.g., using one type in the starter feed, another type in the grower), has been recommended by poultry specialists to help preserve the effectiveness of these valuable compounds.

Furthermore, most of the world’s major poultry markets have not seen a new in-feed anticoccidial in more than 15 years. With no new in-feed products on the horizon, it has become even more important for poultry farms to use available products judiciously and maximize their effectiveness.

Aren’t poultry producers already rotating anticoccidials to preserve their effectiveness?

DW: Yes, they are — and many operations do so quite effectively. But sometimes traditional thinking, old habits, cost considerations and the pressures to achieve optimal short-term performance stand in the way of developing a longer term, sustainable strategy. In other cases, producers may unknowingly rotate to a different product or product combination without realizing it has a similar molecular structure to the anticoccidial they were using previously.

Why does Rotecc advocate developing a long-term plan for coccidiosis management?

DW: The more producers plan ahead, the more rotation options they will have available for effective coccidiosis management. That’s important because it takes time to initiate effective rotation programs that will provide ample rest periods for each class of product. Rotecc encourages producers to consider a 2-year strategy, but even a plan extending 12 to 18 months is a step in the right direction.

Why is coccidiosis so difficult to control?

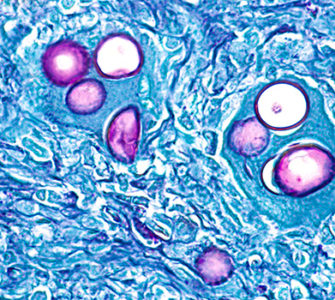

DW: Coccidiosis is caused by coccidia, which are microscopic, protozoan parasites of the Eimeria genus. Coccidia are resilient and reproduce quickly and in large numbers — just one coccidial oocyst (egg) can produce over 500,000 progeny in just 4 to 7 days. The oocysts thrive in warm, humid environments, although coccidiosis is a threat to poultry farms year-round and in arid climates as well. Because the parasites are tenacious and prolific, eradicating them from poultry farms has proved to be virtually impossible.

How does coccidiosis affect flock health and performance?

DW: Acute outbreaks of coccidiosis can result in severe diarrhea and mortality, but fortunately, these situations are rare on progressive poultry farms where anticoccidials are routinely used.

On most commercial poultry farms, the more common problem is low-level, subclinical coccidiosis. This form of the disease can easily develop when products gradually lose their efficacy and slowly erode growth rate, feed conversion and flock uniformity. In layers and breeders, egg production and quality also decline.

Low-level coccidiosis is costly and also predisposes flocks to dysbacteriosis, necrotic enteritis, gangrenous dermatitis and other costly health problems.

How long can ionophores be used without losing effectiveness?

DW: That varies from farm to farm and even house to house. As a general rule, however, the same class of ionophore should not be used for more than 6 consecutive months. At that point, producers should rotate to a different class of ionophore (e.g., monovalent to divalent), a synthetic anticoccidial or even a vaccine.

When should synthetic anticoccidials be considered?

DW: Well-rested, synthetic anticoccidials are highly effective against wild-type strains of coccidia that can emerge when other in-feed anticoccidials lose their effectiveness. When used judiciously, a synthetic anticoccidial can help “press the reset button” on a coccidiosis-management program and let producers get a fresh start on a new rotation strategy.

One caveat: Synthetics have been shown to be highly prone to resistance, so it is important to use them judiciously and budget ample rest time in between treatments. For example, if using a synthetic anticoccidial as part of a clean-up program targeting field strains of Eimeria, it’s best to limit its use to no more than 3 months. If the synthetic product is used in a shuttle program with another type of anticoccidial, up to 4.5 months might be acceptable. Either way, resting the synthetic anticoccidial for as long as 20 months is often recommended to preserve its efficacy for future flocks.

Is vaccination part of the Rotecc strategy?

DW: Absolutely. Coccidiosis vaccination is widely used in the breeder and layer segments of the industry where long-term immunity is required, but most broiler operations use it today in at least a portion of their flocks.

With vaccination, chickens receive a controlled dose of live coccidial oocysts to stimulate their natural immunity against coccidiosis. When administered effectively either in ovo or at the hatchery, vaccines can help provide good protection against the disease while allowing producers to rest all in-feed anticoccidials.

Coccidiosis vaccines seed poultry houses with live coccidia oocysts that are highly susceptible to traditional in-feed anticoccidials. Consequently, vaccination helps restore the effectiveness of some feed medications in subsequent flocks, which has been demonstrated in studies.3,4

What’s a good example of a coccidiosis-management program employing the principles of Rotecc?

DW: There’s no blanket or best program for coccidiosis control, but a typical, 12-month program built on the principles of Rotecc might begin with a monovalent ionophore, followed by a vaccine, a divalent ionophore, a synthetic anticoccidial for clean up and then a monovalent glycoside ionophore.*

A 2-year program would be even better because it would allow more variation. For example: Use an ionophore/chemical combination, followed by vaccination, an ionophore from a different class and then a single chemical.

Is a long-term strategy using more products and combinations more difficult to manage?

DW: No. Rotecc outlines a 12- to 24-month program tailored to suit each operation’s needs and objectives. The program can also be revised midstream to address unforeseen circumstances or changes in production goals or management. Zoetis representatives will work with producers to keep their program in line with their needs.

Will the Rotecc strategy affect feed-mill management or require more time or labor?

DW: No, product rotation is already a common practice for commercial poultry farms and feed mills. Rotecc simply provides a long-term, strategic plan that should ease management and give operations more flexibility with time.

*Monovalent glycoside ionophores are not available in the US market.

1Lillehoj, H.S. 2006. Functional genomics approaches to study host pathogen interactions to mucosal pathogens. Proceedings of the Korean Society of Poultry Science Meeting, Nov. 10, Suwon, Korea.

2Cracking down on poultry disease with egg yolk. Agriculture Research. 2012 July;60(6):9. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service.

3Peek, HW, Landman, WJ. Higher incidence of Eimeria spp. field isolates sensitive for diclazuril and monensin associated with the use of live coccidiosis vaccination with paracox-5 in broiler farms. Avian Dis. 2006 Sep;50(3):434-9.

4Williams, RB. Anticoccidial vaccines for broiler chickens: pathways to success. Avian Pathol. 2002 Aug;31(4):317-53.

Posted on February 28, 2014