Fresh approach to coccidiosis needed to tackle increase in broiler gut damage

Changes in the behavior of one of the most important coccidial pathogens means poultry producers should take a fresh look at how they deal with the parasite.

Eimeria maxima — one of the three main Eimeria parasites that cause coccidiosis in broiler chickens — has traditionally peaked in birds at around 35 days of age (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Traditional development of Eimeria species challenges through a broiler grow out

However, intestinal-health sessions carried out for five different broiler integrators in the UK over a 4-year period have shown that many broiler flocks are becoming infected by E. maxima earlier.

The shift in timing means that E. maxima — widely considered the most economically significant coccidial pathogen in broilers — rears its ugly head at the same time as other infections, such as E. acervulina.

According to Stuart Andrews, PhD, former technical manager at Zoetis UK, this increased infection pressure could result in increased intestinal damage in some flocks.

‘Mixed challenge’

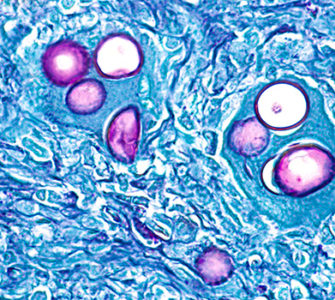

“About 20 years ago, E. maxima typically peaked in broilers at around 35 days of age, but evidence from the field indicates that it has advanced, and with careful microscopic analysis we are now seeing it peak much earlier — any time between 19 and 29 days of age,” Andrews says (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Photo of a high level of E. maxima infection (too many parasite stages to accurately count) in a 19-day-old broiler. This level of infection caused significant damage to the bird’s intestine.

The data collected suggests that the challenge curve of E. maxima has shifted to the left, with the peak challenges affecting birds at earlier ages.

“It often means that in this period, birds are now facing a significant mixed challenge from different Eimeria species in the same part of the mid-intestine, which has implications for bird health, welfare and productivity.”

The change in timing was initially identified during a 2-year-long period (2014-2015) in which Zoetis scientists took scrapings from the mucosa of the mid-intestine of birds across more than 80 broiler farms (many visited on more than one occasion) located in different geographical regions of the UK.

It is uncertain exactly why E. maxima infections are occurring earlier, Andrews says. However, it may partly be due to an evolution in the parasite or changes in its relationship with birds — as well as a change in the genetic make-up of the birds themselves.

Growing resistance

But another significant factor is likely to be growing resistance to some coccidiosis treatments used for extended periods, underscoring the need for producers to reassess how they treat their flocks.

“A lot of broiler farmers are relying on ionophores in their programs, and there’s often a reluctance to rotate,” he adds. “There’s a real possibility that we are seeing resistance build-up.”

One of the solutions, Andrews says, is to try to rotate products more frequently to reduce the risk of resistance developing.

“Simplistically, if you are using an ionophore, I believe we need to restrict its duration of use to about 6 months, after which it — and any other ionophore from the same class — should be rested for at least 6 months. And when you’re deciding what to switch to, make sure you select a product from a different anticoccidial class (Figure 3).”

Figure 3. Switch between anticoccidial classes to minimize chances of cross-resistance. The wider the arrow between products, the greater the chance of developing resistance.1-5

“In other words, if you are using a monovalent ionophore, then switch to either a divalent ionophore or to a synthetic (also referred to as chemical) which will have a different method of action against the coccidia. Use of an anticoccidial vaccine may also be considered for inclusion in such a rotation program,” he adds.

Diagnosis challenge

Regardless of treatment options, however, Andrews concedes that one of the biggest challenges facing producers is identifying the presence of E. maxima in the first place.

Diagnosis is traditionally made by post-mortem examination, where lesions are scored from 0-4 using the Johnson and Reid system.

However, signs of infection, which include small red petechiae on the serosal surface of the mid-intestine, are not always easy to see, and in some cases may not even be present.

What’s more, signs of dysbacteriosis are very similar to E. maxima infections, meaning mild to moderate E. maxima infections can be overlooked.

Coupled with a general lack of awareness about E. maxima among producers, it means the issue is significantly under-reported, Andrews says.

E. maxima surprise

“Although we are seeing an increase in gut damage, by and large birds are performing reasonably well, so farmers are often surprised when we identify an E. maxima problem.

“But the condition can have significant impacts on weight gain and feed conversion, not to mention causing longer-term health issues which then require antibiotics to treat, so it’s important it’s not left untreated.

“The challenge is to get them to understand that if they can control E. maxima more effectively, then birds will perform even better,” Andrews says.

To improve diagnosis, and help producers step in with treatments sooner, Zoetis has traditionally used a modified Johnson and Reid system — and Andrews and his team have used the modified system intensively, with revealing results.

Traditionally, six birds from an individual shed on a farm are culled and scored depending on the number of lesions on the serosal surface of the mid-intestine. Scores of 3 or 4 are clear-cut, but the modification is that with scores of 1 or 2, gut scrapings are examined under a microscope to confirm the presence of E. maxima endogenous stages.

Increased testing

With the modified technique, mucosal scrapings are taken from the mid-intestine region of every bird with significant fluid or orange or pinkish mucus in the intestinal lumen, regardless of whether petechiae are present, and are checked under a microscope for E. maxima oocysts and gametocytes.

In initial tests of 108 birds across 18 UK farms, just 1.9% of birds examined would have scored positive for E. maxima with the traditional scoring system, Andrews says. But with the new increased testing technique, 39% of the total sample tested positive.

“We have now seen similar results from tests on a total of 87 different company and contract broiler farms (representing more than 174 different poultry sheds) — many farms visited on more than two occasions — in the UK since 2014 up until early 2018,” he adds.

The message for producers, Andrews says, is to reassess how often they take intestinal scrapings so that they get a clearer understanding of their farm’s health challenges and can plan appropriate strategies.

“Taking scrapings is time-consuming, and if producers don’t think they have a problem they are reluctant to do it. But getting into that habit — and training and educating staff to think about it too — is important,” He adds.

Welfare implications

In the long-term, Andrews says additional basic research is urgently needed to help the industry understand what is going on in poultry sheds and what the implications could be for wider animal health and welfare.

“Welfare is rarely mentioned in relation to coccidiosis, but it has to be considered alongside the longer-term health implications,” he says.

“Once you get significant damage you can see bacteria getting into the gut, which then often require antibiotic treatment.

“As the industry is continuing to search for ways to limit antibiotics use, this is an area we really need to look at more seriously.”

1. Bedrník P, Jurkovi P, Kuera J, Firmanová A. Cross Resistance to the Ionophorous Polyether Anticoccidial Drugs in Eimeria tenella Isolates from Czechoslovakia. Poult Sci 1989 Jan.1;68(1):89-93, https://doi.org/10.3382/ps.0680089

2. Chapman HD. Biochemical, genetic and applied aspects of drug resistance in Eimeria parasites of the fowl. Avian Pathol. 1997;26(2):221-244. DOI: 10.1080/03079459708419208

3. Chapman HD, Jeffers TK, Williams RB. Forty years of monensin for the control of coccidiosis in poultry. Poult Sci. 2010 Sep. 1;89(9):1788-1801. https://doi.org/10.3382/ps.2010-00931

4. De Gussem M. Coccidiosis in poultry: review on diagnosis, control, prevention and interaction with overall gut health.” in Proceedings of the 16th European Symposium on Poultry Nutrition, Strasbourg, France, 2007. 253-261.

5. Weppelman RM, Olson G, Smith DA, Tamas T, Van Iderstine A. Comparison of Anticoccidial Efficacy, Resistance and Tolerance of Narasin, Monensin and Lasalocid in Chicken Battery Trials. Poult Sci. 1977 Sep. 1;56(5):1550-1559. https://doi.org/10.3382/ps.0561550

Posted on November 28, 2018