Home for the holidays? Poultry vet urges ‘aseptic technique’ in the kitchen

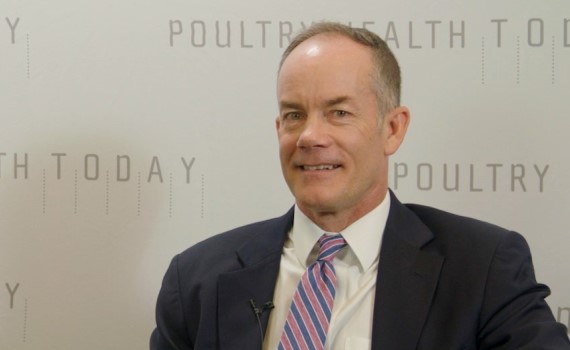

By Robert O’Connor, DVM, MAM

Senior vice president

Foster Farms

Many years ago, during my clinical year of veterinary school, I learned about the aseptic technique necessary to prep for and perform surgical procedures.

Our surgery professor, Dr. Dorn, would silently observe each of us as we rinsed, soaped and disinfected our hands. He carefully watched us don surgical gloves and gowns. If there was any infraction — any break in “aseptic technique” — he would ring a bell. Like Pavlov conditioned his dogs to associate a bell with food, Dr. Dorn conditioned us to associate the bell with poor aseptic technique. Those lessons are hard to shake.

More than 2 decades later, I’m a veterinarian, but I never get near a surgical suite. In fact, my career path has led me away from the realm of live animals. I’m a poultry veterinarian who practices population medicine. For most of the past decade, I have worked primarily on control of pathogens in raw, finished poultry products that can make people sick.

Professional nemeses

The most formidable challenges of my veterinary career in food safety can be boiled down to the two primary foodborne pathogens of poultry: Salmonella and Campylobacter. I consider them my professional nemeses. I recommend various interventions to contain these pathogens during live-poultry production and at processing. At home in my kitchen, however, I practice and preach aseptic technique, which I consider the most critical intervention for preventing human foodborne illness. And I still hear Dr. Dorn’s bell.

I regularly eat meat and poultry products. I know well the risks faced when bringing raw animal protein into my kitchen. I think about the maximum limits of Salmonella permitted by USDA’s Food Safety and Inspection Service. I understand too well that raw meat and poultry are not sterile. I recall Dr. Dorn’s admonition that breaking aseptic technique is all too easy for the inexperienced and that the key to ensuring adherence to aseptic technique is strict reinforcement and training.

As a consumer, it’s my responsibility to make sure raw meat and poultry are safe to eat by cooking it thoroughly enough to issue a lethal blow to any pathogens lingering on the product. But thorough cooking isn’t enough.

After reading interviews with patients who have suffered foodborne illnesses, I would venture to say the major cause of foodborne salmonellosis is the mishandling of raw meat and poultry versus failure to hit the proper cooking temperature.

Consider infant patients with foodborne illness whose parents say the child ate only ready-to-eat baby food. The infant never consumed the rest of the family’s meal of meat or poultry and wasn’t exposed to undercooked food. Well then, how did that baby get sick? Dr. Dorn’s bell rings loudly.

Avoiding cross-contamination

By aseptic technique, I mean preventing cross-contamination. In my opinion, that is much harder to accomplish than issuing that lethal blow of cooking away pathogens.

Human pathogens such as Salmonella and Campylobacter are not normal flora within the home kitchen. Instead, these bacteria arrive as part of the whole body or muscled parts of the animal brought home from the supermarket. I consider these products “radioactive,” requiring handling that prevents “radioactive” contamination of physical vectors in the kitchen. (Now, I’m well aware that the food products we bring home from the grocery store aren’t really radioactive, and radioactive isn’t a word that food-industry marketers are going to like — but a little levity is more likely to draw attention.)

In my home kitchen, I approach aseptic technique with the same vigor I would use if I were preparing a surgical suite. Forethought and preparation are essential. I prep my kitchen worksite before ever transferring the meat or poultry product from the refrigerator, and I consider my hands to be a major potential source of contamination.

- I use warm water and soap to thoroughly clean my hands. Once clean, I avoid touching anything that might spoil their pristine condition.

- I preemptively lay out disinfectant wipes on the counter and take care not to touch them once my hands become “radioactive.”

- I don’t wear surgical gloves, but I do put on latex gloves. I fit them over my clean hands.

- I open the drawer that contains the waste-disposal bin. I don’t want to touch that handle once my hands are contaminated. I place a small plastic bag, open, inside the trash bin.

- I place the bakeware or frying pan on the counter or stovetop. If I’m using oil for the recipe, I pour it into the pan.

***** NOTE: I have not touched the meat or chicken product/package yet! *****

- With clean, gloved hands, I open the refrigerator door and retrieve the package of raw product. My hands are now potentially contaminated.

- It’s my elbow that I use to close the refrigerator door, not my gloved hand.

- I puncture the package with a fork and put the product into the bakeware or pan.

- As per recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), I do not rinse the product for fear of splattering contaminated water droplets, leading to widespread “radiation” disbursement!

- I dump all packaging material into the small plastic bag within the trash can, including any liquid the package contains. (I don’t dump liquid in the package into the sink because it too could splatter when I rinse the sink, contaminating nearby surfaces.)

- Once the product is cooking and the pathogen lethality step is underway, I carefully remove my gloves. My left gloved hand removes the glove on my right hand. Then, using my ungloved right hand, I scoop my fingers underneath the left glove at the wrist and push forward, turning the glove left inside out. Both gloves are discarded into the trash-can bag.

- For extra safety, I use disinfectant wipes to clean anything that might have possibly been contaminated: countertops, the handle for the drawer containing the trash can, the faucet and lever for the sink and the surface inside the refrigerator where the meat or chicken was located in the raw state. Only then do I move on to preparing the rest of the meal — salad, vegetables, potatoes.

Maybe I’m paranoid, but it’s better than becoming a human salmonellosis case statistic. Aseptic technique will also prevent foodborne illness from Campylobacter and probably other pathogens as well.

Teaching the masses

It’s widely known that thorough cooking is important to prevent foodborne disease, but can the average consumer be taught aseptic kitchen technique?

Based on experience with my three children, I would say yes. For years, my kids watched me prepare the Thanksgiving turkey for its entry into the oven. They saw me prepare raw chicken for its transformation into my favorite dish — chicken parmesan. As a result, they are well-versed on the necessity of aseptic technique in the kitchen.

Consumers certainly shouldn’t be frightened away from eating meat proteins, but they need to be taught about aseptic technique.

The US poultry industry spends millions and millions of dollars annually on field and processing-plant interventions to reduce the levels of Salmonella in poultry meat. It’s not money spent in vain. However, the annual number of salmonellosis cases remains pretty steady.

Perhaps a concerted media “blitz” about aseptic technique needs to be made, funded by both the poultry industry and the government. It could be educational and entertaining and, in my opinion, may be the most powerful tool we have to reduce the incidence of human foodborne illness.

Another avenue to explore is teaching aseptic technique in high school health classes. After all, Salmonella and Campylobacter are zoonotic diseases. Students could be taught that while chicken and other meats are a great source of protein, care is needed when handling these products in the kitchen. A detailed curriculum could be easily provided by the industry or the CDC for teachers to use.

Let’s remember the wise adage that if a current course of action doesn’t bring about the desired change, a change needs to be made. Whether it’s a media blitz aimed at the general public or a school curriculum, specifics about aseptic technique need to be provided because the cliché “just cook it” isn’t enough.

Editor’s note: The opinions and advice presented in this article belong to the author and, as such, are presented here as points of view, not specific recommendations by Poultry Health Today.

This article originally appeared in Poultry Health Today in 2019. We thought our readers would find it useful as they prepare for their holiday feasts.

Posted on November 11, 2022

We’re glad you’re enjoying

We’re glad you’re enjoying